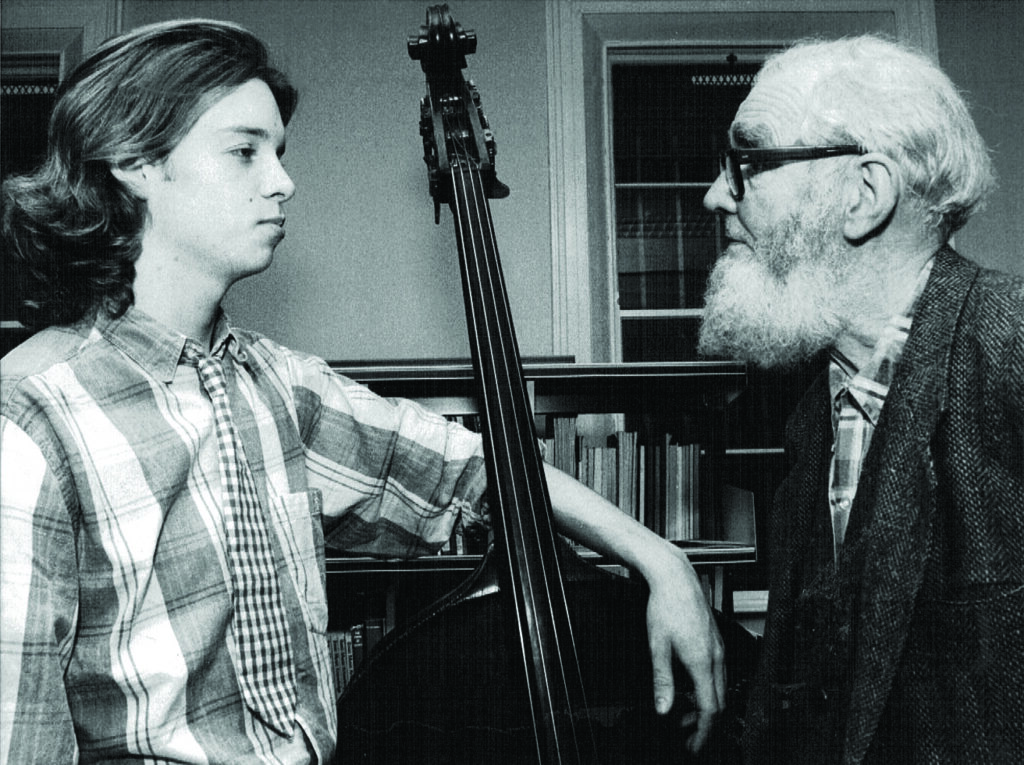

My grandfather Joseph Groocock took a teaching job in Dublin in his early 20s and never returned to England. Meeting my grandmother had something to do with that – they quickly established a family with 5 children in a rickety cottage in the Dublin mountains. He found that his brand of scholarliness, eccentricity and humour was welcomed and apart from secondary-school teaching he found receptive audiences for lectures on music appreciation and his primary love: educating music students in fugue and counterpoint. His palpable joy in sharing Bach’s work with young people was matched by his genuine delight in their company; this was reciprocated and he was adored by three generations of music students in Dublin, including many of my professional colleagues. Although some of those students regretted that his seeds of wisdom fell on stony ground (Bach scholarship isn’t for everyone) they all loved his classes and his infectious enthusiasm.

Joe also wrote music in various styles to fill a need as it arose. An early success was his whimsical musical Jack and Jill and the Drainpipe – written for the boys at his school to perform a bespoke show. A much later composition was his 1985 Sonata for cello and piano, written for his second wife to play at home with him. This piece is greatly indebted to Brahms but is also gently sentimental and energetically jolly; it’s quite the self-portrait, in its mix of scholarship and whimsy. The 2020 lockdown was my opportunity to finally engage with this sonata and to see how it might work on my instrument, the double bass.

It turns out to be a terrific double bass sonata. Acknowledging that the piano part was such a delightful expression of his musical self, I refrained from tweaking it in any way. So I was obliged to choose carefully the registers into which the bass part was transposed. The result is a piece which uses the whole compass of the instrument, singing happily in the cello’s range but extending to the lowest register of the bass at judicious moments. Because of the lockdown, a performance was not a current option and so I fell on the idea of making a recording of it with the wonderful pianist Gary Beecher.

In the back of my mind I had always thought of making a solo album, I think most musicians will have fleetingly imagined it. But there is never time and in any case, there’s the enormous self-doubt hurdle to overcome: why would anyone be interested? Having my grandfather’s lovely sonata to share gave me a way around the obstacle. What else might I have to offer?

In my years at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama I surprised the composers of the Contemporary Music Society by volunteering to play in their concerts of new music; they were accustomed to having to beg players to engage. But I always liked the adventure of new music and how contemporary composers explored the unique resonant, timbral, textural and percussive possibilities of the bass. The romantic solo repertoire that attempted to meet established modes set by or for violinists generally ignored the strengths of our own instrument, and often failed on a musical level to match the smaller instruments (although outdoing them in spectacular athleticism).

Among other factors, the 20th century identity of the bass in jazz has played a large part in emancipating it, allowing a reimagining of the instrument on its own terms. Certainly the double bass is currently in a golden period as players and composers get to know it better at last. I have premiered lots of unaccompanied pieces by composers from Ireland in my 30 years of professional playing, and there were many I recalled with a feeling that there was more to reveal than I had been able to explore at the time. So the album that quickly took shape was of contemporary music from Ireland, all of which was closely connected with me. The title would of course be The Irish Double Bass.

The pieces display a great variety of techniques and could serve as a guide to what a double bass can do: A resonant theme and variations by Eoghan Desmond uses a detuned low string. My grandaddy’s gracious 3-movement sonata with piano. A jig by John Kinsella spans the whole fingerboard and beyond. Ian Wilson’s creative use of a unique scordatura generates colourful clouds of natural harmonics. An energetic take on Norwegian folk fiddling by Kevin O’Connell. A new commission from Deirdre Gribbin begins with a passage employing a pair of tea-spoons like dulcimer hammers. Ryan Molloy treats the bass as a giant strung bodhrán. Judith Ring gives an epic setting of timbral explorations. And to conclude, I sing a favourite Irish song to my own bass accompaniment.

It’s rare to hear a bass in the spotlight, and to get up close like this is really rewarding. The bass adds gravy to an ensemble, making everything else sound better, but it’s a more fascinating sauce than you may have realised. And to players of the smaller string instruments, it can reveal things that are not often considered; the low pitch and string length allows the invocation of upper partials to be precisely controlled for colour. It’s beautifully recorded by Laoise O’Brien and Ben Rawlins of Jiggery Pokery Productions.

I don’t seek to define the Irish double bass, but to deliver a personal document of where the double bass is at, in Ireland: it’s appreciably Irish but, like the country itself, no longer inward-looking. Like Ireland, the double bass is increasingly confident, taking its place on the broader stage, sharing its unique qualities with no need for special pleading for notice or approval.

In memory of John Kinsella, who passed away this month. A national treasure and a lovely human.

The Irish double bass can be downloaded from bandcamp.com, the CD purchased from cmc.ie, or it can be found on streaming services.

This album was made with the support of the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sports & Media.

This article was published in the Strad magazine online, 24/11/2021 https://www.thestrad.com/playing-and-teaching/in-search-of-the-irish-double-bass/14019.article